CS330 Learnings | Introduction and Overview

This course (officially CS330: Multi-Task and Meta-Learning) has been taken by Prof. Chelsea Finn at Stanford. It deals with an in-depth analysis of multi-task and meta-learning, along with discussions on the practical applications of these concepts in various fields (RL, etc). The course is free to audit online with lectures available on YouTube.

Why do I have blog entries on a course that already has an amazing instructor, free online lecture recordings, and slides? Well, I aim to do two things with this series: Firstly, I believe that these articles can serve as a good “recap” for the material taught in the course (so you can refer to these as notes). These are also fairly elaborate for those that do not (maybe) want to watch hour-long lectures and still understand the concepts to a decent extent. Secondly, writing these helps me evaluate my understanding of these topics (and so I learn better!). I hope you enjoy this and take away something from it :)

Motivation

Let’s begin by understanding the need for Multi-Task and Meta-learning. Do we really need these seemingly niche concepts? What problems are these trying to solve? Don’t existing approaches solve these problems?

Why is this important?

We wish to understand the working of the human brain by building agents that can learn different skills in real-life settings.

Don’t we already have Deep Learning models for this?

Yes. We already have extremely expressive models that can solve certain tasks efficiently, matching, and even surpassing human-level performance.

What is the problem then?

These agents are “specialists” as they can perform extremely well on single-tasks. However, Single-Task learning is not scalable. When a robot is taught how to use a spatula to place an object inside a bowl, it very specifically learns to use “that spatula” to put “that object” into “that bowl”.

Can’t we just give it more data?

We can. We can actually give it a lot of data, with different kinds of spatulas, different objects to pick, etc. However, this either requires a lot of effort (and time) or is just not possible in certain domains (for example, you cannot collect enough data to predict the occurrence of a rare disease).

So, this is only a problem with small datasets right?

Not really. There are several other problems that exist. Some of them are as follows:

- Building a general-purpose AI system: This system would definitely need to solve more than one task (else it is not general-purpose)

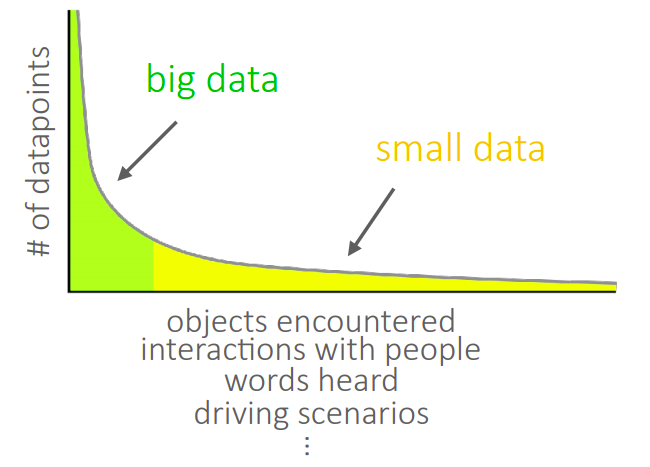

- Long-tail data distributions: Maybe you have a lot of data, but this data is from the “very common instances” lot. There may be several other instances that are not very common. As such your data is said to have a long tail (this is actually more common than you’d think) in contrast to the more popular “Gaussian data picture”.

- Building agents that learn new tasks quickly: And quickly is the keyword here. You cannot “quickly” learn a new task from scratch. As such, you’d need to use (and hence have) some prior experience to learn quickly.

So, how do we solve these problems? This is where the concepts of multi-task learning and meta-learning come into the picture.

Understanding learning

In order to build generalist agents discussed above, we can at best draw inspiration from the way humans learn. Imagine that you need to learn how to drive. How would you go about acquiring this new skill? There will definitely be things that you will have to learn afresh, but you can adapt most of the things from similar experiences in your life before. Would you have to be told what roads are, what directions are, how the steering needs to be held? Most certainly not. You would know these things from your experience as a human so far!

When we train neural networks to learn a new task, we are basically starting with a clean slate. It is analogous to teaching a toddler how to drive! We hence need mechanisms that can instill experience within neural networks to make them better generalists.

What is Multi-task learning?

Given a set of tasks, learn all tasks more quickly and more proficiently than learning them independently. Can this be any set of tasks? Well, no. The simplest constraint for this is that the tasks need to be somewhat similar. If you want to learn how to drive and how to chop onions, learning them together is no better than learning them independently because the tasks are not related at all. If you however want to learn how to ride a bike and how to drive a car, learning one definitely benefits the other.

What is Meta-Learning?

Given experience in some previous tasks, learn a new task more quickly or more efficiently. This follows the same constraint as before requiring the new task to share some similarities with the previous tasks.

What is the difference between the two?

If you have some experience of riding a bike and you are asked to use that experience to learn how to drive a car, that is meta-learning. If instead you are required to simultaneously learn how to ride a bike and drive a car (benefiting from both the experiences), that is multi-task learning.

Lastly, if we wish to compare tasks, how do we define a notion of similarity? In fact, how do we define a task in this respect?

What is a task?

Informally, a task does the following (a formal definition is given in the next lecture):

Given a dataset \(D\) and a loss function \(L\), it optimizes on the loss function \(L\) and outputs a model \(f_{\theta}\) for mapping inputs \(x_{i}\) to their corresponding outputs \(y_{i}\) (where \((x_{i}, y_{i}) \in D\)).

Hence, two tasks would be considered different if they differ in either the dataset \(D\) or the loss function \(L\) or both.

Multi-task and Meta-Learning require tasks to share some structure in the sense that even if they do not appear similar on the surface, they do have certain underlying similarities. For example, opening a can and uncapping a water bottle are different tasks on the surface but use the same principle in practice.

Doesn’t Multi-Task Learning reduce to Single-Task Learning?

You could aggregate data from all the tasks to create a huge dataset (\(D = \bigcup D_{i}\)), sum all the individual losses to optimize for an aggregate loss (\(L = \sum L_{i}\)) and then create a single model for all the tasks, right? Yes, you can (and that is one approach to Multi-Task Learning). However, we can often perform better with the knowledge that the data is coming from different tasks.

As neural networks are universal function approximators, won’t they eventually figure out the differences between the tasks?

They would. But that would probably take a lot of time as the function would then become too complex to optimize for.

Why study this now?

- These algorithms are playing a fundamental, and increasing role in machine learning research. This is evident from the number of search queries and citations of associated papers.

- Their success will be critical for the democratization of deep learning. Essentially, deep learning so far has only been able to (mostly) excel at tasks with huge amounts of data, which is not a very practical component. We need models that can work with much lesser amounts of data and still excel at these tasks and many more!

That concludes this article (and lecture 1 from the course). Please let me know if there are other things that should have been addressed and also potential errors that could have crept in. Thank you for taking the time to read this article (I sincerely hope it helped you in some way).

References

[1] Video for Lecture 1 (Introduction & Overview)

[2] Slides for Lecture 1 (Introduction & Overview)